Catheter-associated urinary tract infections in veterinary medicine (CAUTI)

Fact sheet

CAUTI in veterinary medicine

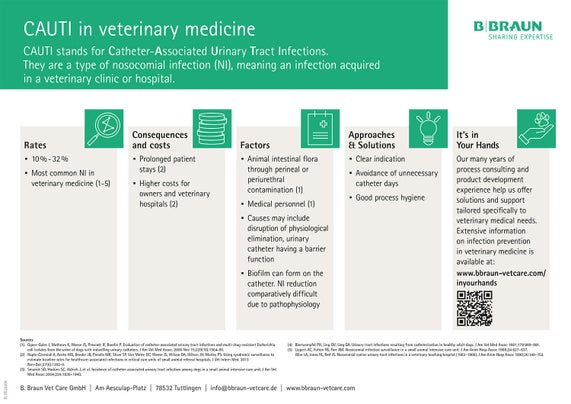

CAUTI stands for Catheter-Associated Urinary Tract Infections. They are a type of nosocomial infection (NI), meaning an infection acquired in a veterinary clinic or hospital.

Urinary tract infections are among the most common NI/HAI in veterinary medicine with an incidence of 10 to 32 percent. [1-5]

One cause for an underlying increased incidence might be that the urinary catheter is disturbing the physiological drainage and barrier function – the urinary bladder is normally fully deflated during micturition and the formation of a mucus layer on the urinary epithelium provides further protection. The urinary catheter prevents the bladder from emptying completely. In addition, urine collects at the bottom of the bladder in the area of the balloon. When placing the catheter, micro lesions can develop in the urethral epithelium and the integrity of the mucus layer can also be impaired. Placing the catheter may also allow initial bacteria of the periurethral flora to enter the bladder.

Shortly after the catheter has been inserted, a biofilm forms on both the inner and outer surface of the catheter in which the bacteria can multiply.

The likelihood of a urinary tract infection in veterinary medicine increases by 20 percent with every year of life, by up to 27 percent per catheterization day and by 45 percent if the dog is on antibiotic therapy. [6] In human medicine, 17 percent of all nosocomial bacteremias are caused by catheter-associated urinary tract infections. Urosepsis is associated with a mortality of 10 percent. [7]

The pathogen reservoir of CAUTI is primarily the endogenous flora of the gastrointestinal tract and the urogenital tract, but also other sources of infection due to interruptions in asepsis when inserting the catheter. [8] Reducing these nosocomial infections (NI) is a challenging task. Nevertheless, a reduction in CAUTI can also be achieved here by strict indication and avoidance of unnecessary catheter days, as well as good basic and process hygiene.

[1] Ruple-Czerniak A, Aceto HW, Bender JB, Paradis MR, Shaw SP, van Metre DC et al. Using syndromic surveillance to estimate baseline rates for healthcare-associated infections in critical care units of small animal referral hospitals. J Vet Intern Med 2013; 27(6):1392-9.

[2] Lippert AC, Fulton RB, JR., Parr AM. Nosocomial infection surveillance in a small animal intensive care unit; 1988.

[3] Ogeer-Gyles J, Mathews K, Weese JS, Prescott JF, Boerlin P. Evaluation of catheter-associated urinary tract infections and multi-drug-resistant Escherichia coli isolates from the urine of dogs with indwelling urinary catheters. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2006; 229(10):1584-90.

[4] Smarick SD, Haskins SC, Aldrich J, Foley JE, Kass PH, Fudge M et al. Incidence of catheter-associated urinary tract infection among dogs in a small animal intensive care unit. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2004; 224(12):1936-40.

[5] Biertuempfel PH, Ling GV, Ling GA. Urinary tract infection resulting from catheterization in healthy adult dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1981; 178(9):989-91.

[6] Bubenik LJ, Hosgood GL, Waldron DR, Snow LA. Frequency of urinary tract infection in catheterized dogs and comparison of bacterial culture and susceptibility testing results for catheterized and noncatheterized dogs with urinary tract infections. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2007; 231(6):893-9.

[7] Gould CV, Umscheid CA, Agarwal RK, Kuntz G, Pegues DA. Guideline for prevention of catheter-associated urinary tract infections 2009. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2010; 31(4):319-26.

[8] Hooton TM, Bradley SF, Cardenas DD, Colgan R, Geerlings SE, Rice JC et al. Diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of catheter-associated urinary tract infection in adults: 2009 International Clinical Practice Guidelines from the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2010; 50(5):625-63.